ESSAY Alistair Rider

Since 2006 Cecilia Vissers has been working with anodized aluminum and steel. Her wallmounted sculptures are precision cut from solid slabs of metal, and subjected to complex industrial processes that give them their distinctive patina. The surfaces of the steel sculptures feature cloudy blooms of blue and grey, while the aluminum undergoes up to fifteen different types of treatment, including etching, brightening and sealing. The result is a highly distinctive bright orange hue, which derives directly from the chemical composition of the aluminum.

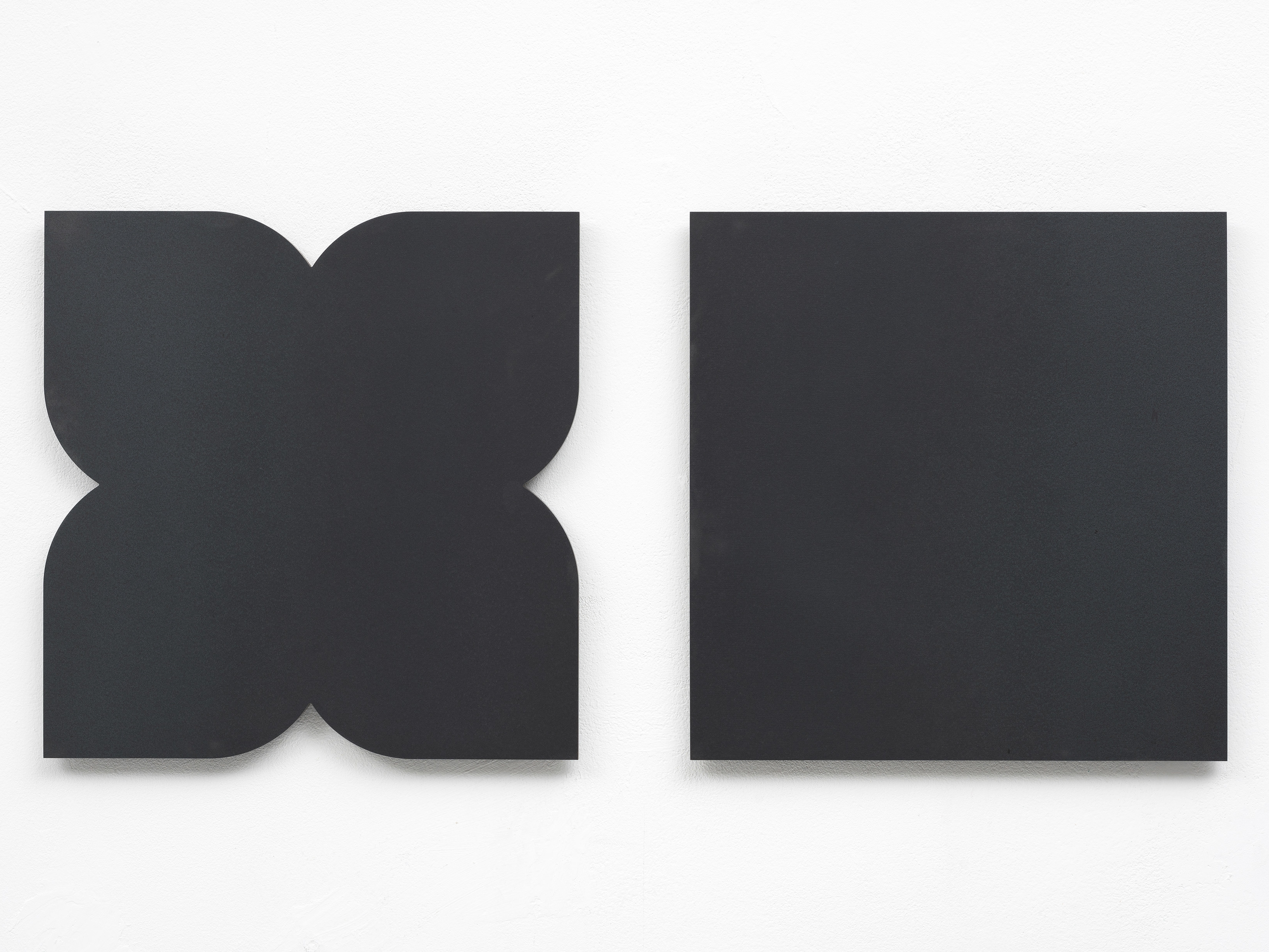

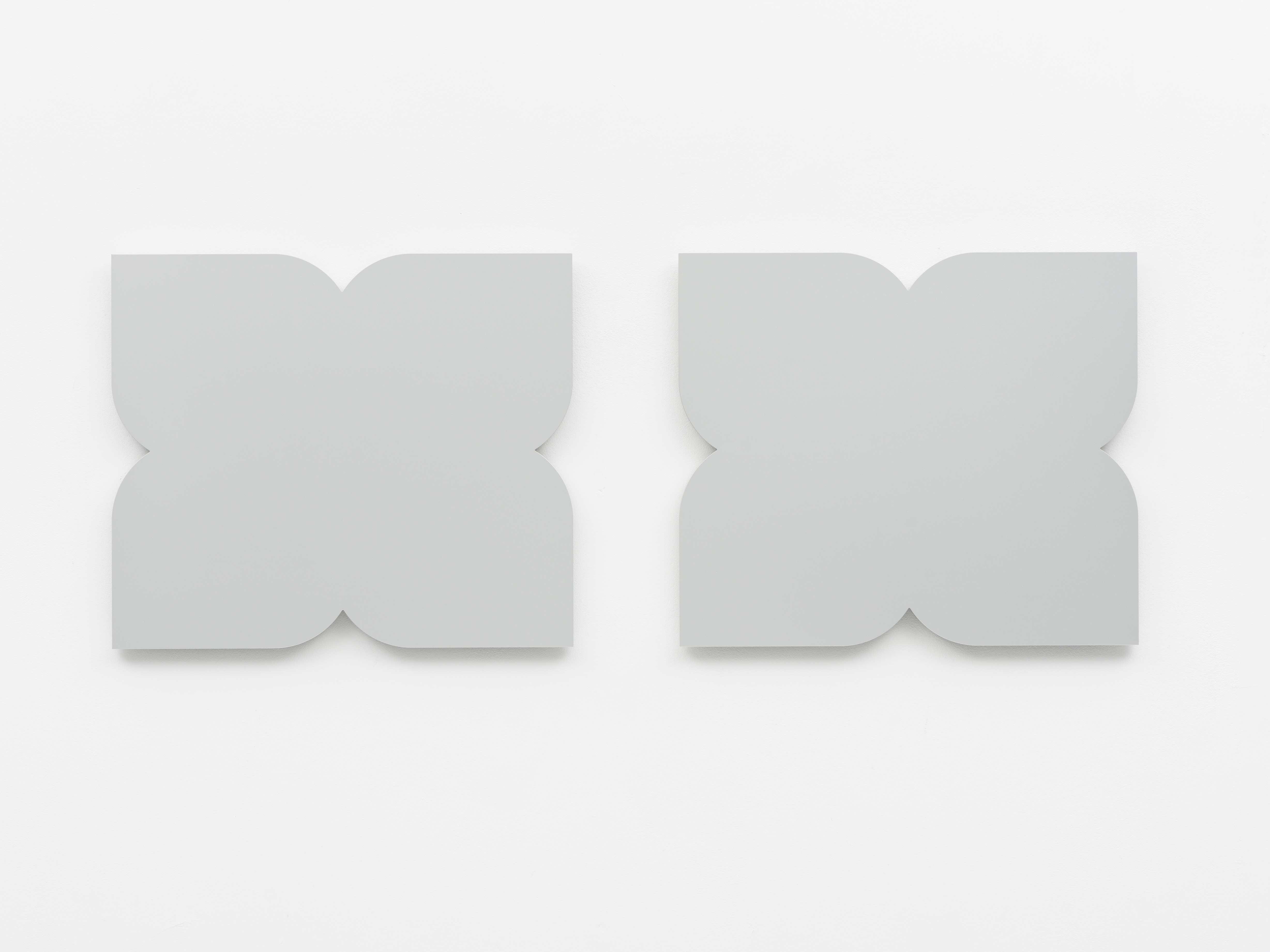

Vissers works closely with specialist metal fabricators in the Ruhr district in Germany, who are able to attain remarkable levels of accuracy in the realization of her designs. Although from a distance these works resemble weightless shapes, they are also extremely heavy objects. Vissers’ commitment to metal dates back to the beginning of her career. When she left art school in the Netherlands she found herself a studio in an old forge. A blacksmith, who was still working in the building, introduced her to the tools of the trade and instilled in her a lifelong fascination with the ancient art of working this material. One of her earliest attempts to slice into steel plate involved using a powerful hand-held jigsaw. She made two incisions, which resulted in a notch being removed from one of the longer sides. The curved cut, which jigsaws are specially designed to produce, yielded a striking shape, which she chose to explore in her future work. It has become a decisive hallmark of her mature style and the majority of her metal reliefs incorporate modest excisions from square and rectangular forms.

Vissers frequently creates reliefs in pairs or series, and, by varying the size and location of the cuts, she develops nuanced, contrapuntal rhythms. The commitment to absolute technical precision, which these sculptures exhibit, would undoubtedly have appealed to the exacting production standards of Donald Judd. Vissers’ approach to making art has much in common with the pared down language of American minimalism, with which artists such as Judd and Dan Flavin are now associated. But her work also belongs to an older tradition of geometric abstraction that derives inspiration from the natural world.

Vissers is particularly drawn to the rugged coastal landscapes of Scotland and Ireland, and has often made associations between the formal properties of her sculptures and the wild qualities of these environments. These correlations exist for her at an experiential level. She has spoken, for instance, of the simple challenge of standing upright in high winds on a narrow coastal path in County Mayo in Western Ireland, and has suggested that her works also explore similar physical sensations relating to the attainment of balance and steadiness.

When she uses symmetry in her relief sculptures she is not invoking idealized, otherworldly values. She is addressing our tangible experiences of actual topographies, and the sublime joys that we encounter when immersed in the wind and the weather. Vissers lives and works in Sint-Oedenrode in the Netherlands.

Dr. Alistair Rider is an art historian at the University of St. Andrews UK, 2015

INTERVIEW WITH Brian Edmonds & Tina Ruggieri

publication 'eraser 3' 2021

Brian Edmonds: In a previous conversation, you mentioned how you are influenced by the landscape. Is there a particular landscape or topography you look to? Is it emotional or visual? Do you keep a sketchbook or take photos?

Cecilia Vissers: Although my steel sculptures appear to be abstract, each piece invokes my own landscape experience. I have a fascination for remote and wild places like Achill Island, on the west coast of Ireland, and the Scottish Highlands. These landscapes reveal a fundamental truth. The power and serenity of nature brings me closer to the essence of life. Knowledge emerges from these experiences in nature rather than from reason. The influence of the landscape on my work is both visual and emotional. The emotional sensation of standing upright in high winds on a narrow coastal path is what we feel right away before the mind has time to come in and consciously analyze the experience. My work is about that open feeling, a feeling of freedom. Intuition is our first instinct and the highest form of intelligence. It leads me to where I need to go in my process of making art. I don’t use a mathematical system. It is more important to look, register, and adapt very carefully. My black and white photographs of landscapes are part of my process of making new work. The photos, taken during my travels, are my sketches and serve as a memento of my landscape experiences. Most titles refer directly to the places I love. For example, ‘Duvillaun’ is the name of a cluster of islands lying South to the coast of North Mayo in Ireland and ‘Blue Mull’ refers to the strait between Shetland’s North Isles.

BE: Do you seek to create a narrative using specific shapes, titles, or color? I’m interested in how the works are shown. Are works exhibited in close proximity or spaced further apart? Are you looking to create a narrative?

CV: My sculptures are arrangements of rectangles and square plates; some plates show curved excisions from their edges. They hang exactly 10 millimeters apart from the wall, which accentuates the thickness of the steel or aluminum. There is an interaction between the parts of the artwork that have excisions and the parts that are rectangular. The rectangular parts are the unaffected (whole) parts. By using just one color I accentuate the spatial arrangement and the rhythm. I like to use orange because it draws attention and generates positive energy. Most of my works come in pairs or a series. By varying the size and location of the cuts, as well as by controlling the distances between the plates, I create rhythm and a narrative. Quite often, the space in between the plates is a potential space; the starting point for my next artwork. Richard Serra said it very well, “work comes out of work.” I see a connection between everything, every small intervention or shift has consequences for the total experience of the artwork and its surrounding space. When I exhibit my work, I see all exhibited works in space as a whole. You can say it’s a conversation between the works themselves. One of the most impressive works of art I know is the 30-minute-long movie ‘The Way Things Go’ (1987) by the Swiss duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss. The film presents a sequence of events, if one object moves, a chain reaction occurs. This interconnectedness between individual objects is fascinating, nothing exists in isolation.

Tina Ruggieri: Can you discuss your reference to nature and how it differentiates from the ideas of minimalism?

CV: My sculptures have much in common with the pared down language of American minimalism. I admire the work of minimalist artists such as Judd, Andre, Kelly and Flavin. The work of Ted Stamm is also worth mentioning. I admire his clear and consistent form language as well as the way his work is installed in space. My special interest goes to the work of those artists who balance between the second and third dimension. There are more similarities than differences between the ideas of the minimalists and my work. Minimalism is about the simplicity of forms in space. Many minimalists have a close relation to the natural landscape or the urban landscape. Robert Mangold is a good example. When he first moved to New York he felt attracted to the buildings and the empty spaces between the buildings. He noted that the bridges and the roads are not only structures, but they’re also forms in space. It’s not a secret that the paintings of Kelly are not purely abstract but are representations of forms he found in nature. In 2012, I visited his Black & White exhibition in the Museum of Wiesbaden, I remember Kelly’s gelatin silver prints of forms in the landscape. A shadow under a bridge, the curved roof of a shed and the structures of farmhouses. Finally, I’ve to mention the work of Donald Judd. On occasion of my solo exhibition at inde/jacobs gallery in Marfa (2015), I visited this small town in the high desert of Texas. I was very lucky to get the opportunity to visit Judd’s remote ranch house, annex studio, ‘Las Casas’ in the beautiful Chinati desert. Back in the seventies, Judd bought this land to protect it and live there with his family.I’m convinced that his love for landscape was an important source of his inspiration. He had a need to withdraw from society and purely focus on his art. The visit was a life-changing experience, seeing Judd’s artwork in the incredible desert light is beyond words.

TR: Can you discuss your interest in steel and aluminum and what first attracted you to this material?

CV: When I went to the Academy of Fine Arts I immediately felt attracted to working in this hard and heavy material. After a visit to the blast furnaces based in the city of IJmuiden, I decided to only work in metal. I saw the intense orange glow of the molten material that was rolled into giant sheets of steel. The hardness of this material is a challenge, you must put a lot of energy into the metal to get something out of it. It also requires specific material knowledge, the forging, the welding, patinating and the knowledge of various tools. The material also has a kind of inexorability, it resists and has a will of its own. Once I put my saw in the metal, the process is irreversible, an error is difficult to fix. I’ve to make a well-balanced choice. First, I make my models in cardboard and hang them on the wall of my studio. Then I make small changes; the curve can shift a few millimeters to the left or right. I also determine the thickness and color of the steel I will use. Even a small change affects the whole. My first studio was an old forge, a very dark and cold place with horseshoes hanging on rusty nails on the beams. The blacksmith taught me how to use the fire, to understand the glowing coals and how to form the steel on an anvil. Later, I focused more and more on industrial processes, I went into long-term collaborations with companies that could execute parts of my work. It’s very important to be present and make sure that everything goes according to my plan. I work with a waterjet company close to my hometown, they cut my designs out of special plates of steel. The director understands my love for steel, when he receives a special plate of steel with an exceptional patina, he decides to call me to come over and look. These collaborations are very important to me. I’m grateful to the people who have so much technical knowledge and patience.

TR: Do you consider yourself a painter or sculptor, or does your work fall somewhere in between?

CV: Without doubt, I consider myself a sculptor. When I have an idea, I can see it in metal. I don’t see clay, wood, plastic, or any other material; it is just metal. The material is the basis. The plates have a ‘patina’, each one very unique. The color of the plates varies dramatically, sometimes it is bluer at the edges and grayer in the center of the sheet. I do a lot of work in series and editions, still, it’s impossible to make an exact copy of a work. Each work has its own patina. Sometimes I use chemicals to intensify the colours and patterns. It is essential to choose the right plate, when I go to the metal supplier, he displays several plates on the floor. Each plate can weigh up to 200kg. Then I select a beautiful plate with an interesting pattern. The plates must be undamaged, each scratch interferes with the final artwork. Some years ago, I applied for a working grant, the members of the commission rated my work as a painting. It indicates that one is inclined to see a painting in an object that is flat and hangs on the wall. This is a misconception. My recent book is titled ‘Flatness in Space’ referring to the flat character of my sculptures and their placing in space.

Tina Ruggieri is an art historian and curator, she lives in Alabama USA

Brian Edmonds is an artist, writer and curator based in Alabama USA